Cheese

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Cheese (disambiguation).

| | This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2011) |

Wheels of Gouda

Cheese consists of proteins and fat from milk, usually the milk of cows, buffalo, goats, or sheep. It is produced by coagulation of the milk protein casein. Typically, the milk is acidified and addition of the enzyme rennet causes coagulation. The solids are separated and pressed into final form.[1] Some cheeses have molds on the rind or throughout. Most cheeses melt at cooking temperature.

Hundreds of types of cheese are produced. Their styles, textures and flavors depend on the origin of the milk (including the animal's diet), whether they have been pasteurized, the butterfat content, the bacteria and mold, the processing, and aging. Herbs, spices, or wood smoke may be used as flavoring agents. The yellow to red color of many cheeses is from adding annatto.

For a few cheeses, the milk is curdled by adding acids such as vinegar or lemon juice. Most cheeses are acidified to a lesser degree by bacteria, which turn milk sugars into lactic acid, then the addition of rennet completes the curdling. Vegetarian alternatives to rennet are available; most are produced by fermentation of the fungus Mucor miehei, but others have been extracted from various species of the Cynara thistle family.

Cheese is valued for its portability, long life, and high content of fat, protein, calcium, and phosphorus. Cheese is more compact and has a longer shelf life than milk. Cheesemakers near a dairy region may benefit from fresher, lower-priced milk, and lower shipping costs. The long storage life of some cheese, especially if it is encased in a protective rind, allows selling when markets are favorable.

Contents[hide] |

Etymology

The word cheese comes from Latin caseus,[2] from which the modern word casein is closely derived. The earliest source is from the proto-Indo-European root *kwat-, which means "to ferment, become sour".More recently, cheese comes from chese (in Middle English) and cīese or cēse (in Old English). Similar words are shared by other West Germanic languages — West Frisian tsiis, Dutch kaas, German Käse, Old High German chāsi — all from the reconstructed West-Germanic form *kasjus, which in turn is an early borrowing from Latin.

When the Romans began to make hard cheeses for their legionaries' supplies, a new word started to be used: formaticum, from caseus formatus, or "molded cheese" (as in "formed", not "moldy"). It is from this word that the French fromage, Italian formaggio, Catalan formatge, Breton fourmaj, and Provençal furmo are derived. Cheese itself is occasionally employed in a sense that means "molded" or "formed". Head cheese uses the word in this sense.

History

Main article: History of cheese

Origins

A piece of soft curd cheese, oven baked to increase longevity

Proposed dates for the origin of cheesemaking range from around 8000 BCE (when sheep were first domesticated) to around 3000 BCE. The first cheese may have been made by people in the Middle East or by nomadic Turkic tribes in Central Asia. Since animal skins and inflated internal organs have, since ancient times, provided storage vessels for a range of foodstuffs, it is probable that the process of cheese making was discovered accidentally by storing milk in a container made from the stomach of an animal, resulting in the milk being turned to curd and whey by the rennet from the stomach. There is a legend with variations about the discovery of cheese by an Arab trader who used this method of storing milk.[4][5]

Cheesemaking may have begun independently of this by the pressing and salting of curdled milk to preserve it. Observation that the effect of making milk in an animal stomach gave more solid and better-textured curds, may have led to the deliberate addition of rennet.

The earliest archeological evidence of cheesemaking has been found in Egyptian tomb murals, dating to about 2000 BCE.[6] The earliest cheeses were likely to have been quite sour and salty, similar in texture to rustic cottage cheese or feta, a crumbly, flavorful Greek cheese.

Cheese produced in Europe, where climates are cooler than the Middle East, required less salt for preservation. With less salt and acidity, the cheese became a suitable environment for useful microbes and molds, giving aged cheeses their respective flavors.

Ancient Greece and Rome

Cheese in a market in Italy

| “ | We soon reached his cave, but he was out shepherding, so we went inside and took stock of all that we could see. His cheese-racks were loaded with cheeses, and he had more lambs and kids than his pens could hold... When he had so done he sat down and milked his ewes and goats, all in due course, and then let each of them have her own young. He curdled half the milk and set it aside in wicker strainers. | ” |

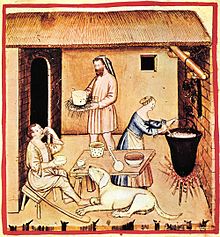

Cheese, Tacuinum sanitatis Casanatensis (XIV century)

Post-Roman Europe

As Romanized populations encountered unfamiliar newly-settled neighbors, bringing their own cheese-making traditions, their own flocks and their own unrelated words for cheese, cheeses in Europe diversified further, with various locales developing their own distinctive traditions and products. As long-distance trade collapsed, only travelers would encounter unfamiliar cheeses: Charlemagne's first encounter with a white cheese that had an edible rind forms one of the constructed anecdotes of Notker's Life of the Emperor.[7] The British Cheese Board claims that Britain has approximately 700 distinct local cheeses;[8] France and Italy have perhaps 400 each. (A French proverb holds there is a different French cheese for every day of the year, and Charles de Gaulle once asked "how can you govern a country in which there are 246 kinds of cheese?"[9]) Still, the advancement of the cheese art in Europe was slow during the centuries after Rome's fall. Many cheeses today were first recorded in the late Middle Ages or after— cheeses like Cheddar around 1500 CE, Parmesan in 1597, Gouda in 1697, and Camembert in 1791.[10]In 1546, The Proverbs of John Heywood claimed "the moon is made of a greene cheese." (Greene may refer here not to the color, as many now think, but to being new or unaged.)[11] Variations on this sentiment were long repeated and NASA exploited this myth for an April Fools' Day spoof announcement in 2006.[12]

Modern era

Until its modern spread along with European culture, cheese was nearly unheard of in oriental cultures, in the pre-Columbian Americas, and only had limited use in sub-Mediterranean Africa, mainly being widespread and popular only in Europe and areas influenced strongly by its cultures. But with the spread, first of European imperialism, and later of Euro-American culture and food, cheese has gradually become known and increasingly popular worldwide, though still rarely considered a part of local ethnic cuisines outside Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas.[citation needed]The first factory for the industrial production of cheese opened in Switzerland in 1815, but it was in the United States where large-scale production first found real success. Credit usually goes to Jesse Williams, a dairy farmer from Rome, New York, who in 1851 started making cheese in an assembly-line fashion using the milk from neighboring farms. Within decades hundreds of such dairy associations existed.[citation needed]

The 1860s saw the beginnings of mass-produced rennet, and by the turn of the century scientists were producing pure microbial cultures. Before then, bacteria in cheesemaking had come from the environment or from recycling an earlier batch's whey; the pure cultures meant a more standardized cheese could be produced.[citation needed]

Factory-made cheese overtook traditional cheesemaking in the World War II era, and factories have been the source of most cheese in America and Europe ever since. Today, Americans buy more processed cheese than "real", factory-made or not.[13]

Production

| | This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2007) |

Curdling

During industrial production of Emmental cheese, the as-yet-undrained curd is broken by rotating mixers.

Some fresh cheeses are curdled only by acidity, but most cheeses also use rennet. Rennet sets the cheese into a strong and rubbery gel compared to the fragile curds produced by acidic coagulation alone. It also allows curdling at a lower acidity—important because flavor-making bacteria are inhibited in high-acidity environments. In general, softer, smaller, fresher cheeses are curdled with a greater proportion of acid to rennet than harder, larger, longer-aged varieties.

Curd processing

At this point, the cheese has set into a very moist gel. Some soft cheeses are now essentially complete: they are drained, salted, and packaged. For most of the rest, the curd is cut into small cubes. This allows water to drain from the individual pieces of curd.Some hard cheeses are then heated to temperatures in the range of 35–55 °C (95–131 °F). This forces more whey from the cut curd. It also changes the taste of the finished cheese, affecting both the bacterial culture and the milk chemistry. Cheeses that are heated to the higher temperatures are usually made with thermophilic starter bacteria that survive this step—either Lactobacilli or Streptococci.

Salt has roles in cheese besides adding a salty flavor. It preserves cheese from spoiling, draws moisture from the curd, and firms cheese’s texture in an interaction with its proteins. Some cheeses are salted from the outside with dry salt or brine washes. Most cheeses have the salt mixed directly into the curds.

Other techniques influence a cheese's texture and flavor. Some examples:

- Stretching: (Mozzarella, Provolone) The curd is stretched and kneaded in hot water, developing a stringy, fibrous body.

- Cheddaring: (Cheddar, other English cheeses) The cut curd is repeatedly piled up, pushing more moisture away. The curd is also mixed (or milled) for a long time, taking the sharp edges off the cut curd pieces and influencing the final product's texture.

- Washing: (Edam, Gouda, Colby) The curd is washed in warm water, lowering its acidity and making for a milder-tasting cheese.

Parmigiano reggiano in a modern factory

Ripening

Main article: Cheese ripening

A newborn cheese is usually salty yet bland in flavor and, for harder varieties, rubbery in texture. These qualities are sometimes enjoyed—cheese curds are eaten on their own—but normally cheeses are left to rest under controlled conditions. This aging period (also called ripening, or, from the French, affinage) lasts from a few days to several years. As a cheese ages, microbes and enzymes transform texture and intensify flavor. This transformation is largely a result of the breakdown of casein proteins and milkfat into a complex mix of amino acids, amines, and fatty acids.Some cheeses have additional bacteria or molds intentionally introduced before or during aging. In traditional cheesemaking, these microbes might be already present in the aging room; they are simply allowed to settle and grow on the stored cheeses. More often today, prepared cultures are used, giving more consistent results and putting fewer constraints on the environment where the cheese ages. These cheeses include soft ripened cheeses such as Brie and Camembert, blue cheeses such as Roquefort, Stilton, Gorgonzola, and rind-washed cheeses such as Limburger.

Types

Main article: Types of cheese

There are several types of cheese, with around 500 different varieties recognised by the International Dairy Federation,[14] over 400 identified by Walter and Hargrove, over 500 by Burkhalter, and over 1,000 by Sandine and Elliker.[15] The varieties may be grouped or classified into types according to criteria such as length of ageing, texture, methods of making, fat content, animal milk, country or region of origin, etc. – with these criteria either being used singly or in combination,[16] but with no single method being universally used.[17] The method most commonly and traditionally used is based on moisture content, which is then further discriminated by fat content and curing or ripening methods.[14][18] Some attempts have been made to rationalise the classification of cheese – a scheme was proposed by Pieter Walstra which uses the primary and secondary starter combined with moisture content, and Walter and Hargrove suggested classifying by production methods which produces 18 types, which are then further grouped by moisture content.[14]- Moisture content (soft to hard)

- Fresh, whey and stretched curd cheeses

- Content (double cream, goat, ewe and water buffalo)

- Soft-ripened and blue-vein

- Processed cheeses

Eating and cooking

At refrigerator temperatures, the fat in a piece of cheese is as hard as unsoftened butter, and its protein structure is stiff as well. Flavor and odor compounds are less easily liberated when cold. For improvements in flavor and texture, it is widely advised that cheeses be allowed to warm up to room temperature before eating. If the cheese is further warmed, to 26–32 °C (79–90 °F), the fats will begin to "sweat out" as they go beyond soft to fully liquid.[19]Above room temperatures, most hard cheeses melt. Rennet-curdled cheeses have a gel-like protein matrix that is broken down by heat. When enough protein bonds are broken, the cheese itself turns from a solid to a viscous liquid. Soft, high-moisture cheeses will melt at around 55 °C (131 °F), while hard, low-moisture cheeses such as Parmesan remain solid until they reach about 82 °C (180 °F).[20] Acid-set cheeses, including halloumi, paneer, some whey cheeses and many varieties of fresh goat cheese, have a protein structure that remains intact at high temperatures. When cooked, these cheeses just get firmer as water evaporates.

Some cheeses, like raclette, melt smoothly; many tend to become stringy or suffer from a separation of their fats. Many of these can be coaxed into melting smoothly in the presence of acids or starch. Fondue, with wine providing the acidity, is a good example of a smoothly melted cheese dish.[21] Elastic stringiness is a quality that is sometimes enjoyed, in dishes including pizza and Welsh rarebit. Even a melted cheese eventually turns solid again, after enough moisture is cooked off. The saying "you can't melt cheese twice" (meaning "some things can only be done once") refers to the fact that oils leach out during the first melting and are gone, leaving the non-meltable solids behind.

As its temperature continues to rise, cheese will brown and eventually burn. Browned, partially burned cheese has a particular distinct flavor of its own and is frequently used in cooking (e.g., sprinkling atop items before baking them).

Health and nutrition

In general, cheese supplies a great deal of calcium, protein, phosphorus and fat. A 30-gram (1.1 oz) serving of Cheddar cheese contains about 7 grams (0.25 oz) of protein and 200 milligrams of calcium. Nutritionally, cheese is essentially concentrated milk: it takes about 200 grams (7.1 oz) of milk to provide that much protein, and 150 grams (5.3 oz) to equal the calcium.[22]Heart disease

Cheese potentially shares other nutritional properties of milk. The Center for Science in the Public Interest describes cheese as America's number one source of saturated fat, adding that the average American ate 30 lb (14 kg) of cheese in the year 2000, up from 11 lb (5 kg) in 1970.[23] Their recommendation is to limit full-fat cheese consumption to 2 oz (57 g) a week. Whether or not cheese's highly saturated fat content actually leads to an increased risk of heart disease is a subject of debate, as epidemiological studies have observed relatively low incidences of cardiovascular disease in populations such as France and Greece, which lead the world in cheese consumption (more than 14 oz/400 g a week per person, or over 45 lb/20 kg a year).[24] This seeming discrepancy is called the French paradox; the higher rates of consumption of red wine in these countries is often invoked as at least a partial explanation.Dental health

Some studies claim that cheddar, mozzarella, Swiss and American cheeses can help to prevent tooth decay.[25][26] Several mechanisms for this protection have been proposed:- The calcium, protein, and phosphorus in cheese may act to protect tooth enamel.

- Cheese increases saliva flow, washing away acids and sugars.

Effect on sleep

A study by the British Cheese Board in 2005 to determine the effect of cheese upon sleep and dreaming discovered that, contrary to the idea that cheese commonly causes nightmares, the effect of cheese upon sleep was positive. The majority of the two hundred people tested over a fortnight claimed beneficial results from consuming cheeses before going to bed, the cheese promoting good sleep. Six cheeses were tested and the findings were that the dreams produced were specific to the type of cheese. Although the apparent effects were in some cases described as colorful and vivid, or cryptic, none of the cheeses tested were found to induce nightmares. However, the six cheeses were all British. The results might be entirely different if a wider range of cheeses were tested.[27] Cheese contains tryptophan, an amino acid that has been found to relieve stress and induce sleep.[28]Casein

Like other dairy products, cheese contains casein, a substance that when digested by humans breaks down into several chemicals, including casomorphine, an opioid peptide. In the early 1990s it was hypothesized that autism can be caused or aggravated by opioid peptides.[29] Studies supporting these claims have had significant flaws, so the data are inadequate to guide autism treatment recommendations.[30]Lactose

Cheese is often avoided by those who are lactose intolerant, but ripened cheeses like Cheddar contain only about 5% of the lactose found in whole milk, and aged cheeses contain almost none.[31] Nevertheless, people with severe lactose intolerance should avoid eating dairy cheese. As a natural product, the same kind of cheese may contain different amounts of lactose on different occasions, causing unexpected painful reactions.Hypertensive effect

Some people suffer reactions to amines found in cheese, particularly histamine and tyramine. Some aged cheeses contain significant concentrations of these amines, which can trigger symptoms mimicking an allergic reaction: headaches, rashes, and blood pressure elevations.Pasteurization

A number of food safety agencies around the world have warned of the risks of raw-milk cheeses. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration states that soft raw-milk cheeses can cause "serious infectious diseases including listeriosis, brucellosis, salmonellosis and tuberculosis".[32] It is U.S. law since 1944 that all raw-milk cheeses (including imports since 1951) must be aged at least 60 days. Australia has a wide ban on raw-milk cheeses as well, though in recent years exceptions have been made for Swiss Gruyère, Emmental and Sbrinz, and for French Roquefort.[33] There is a trend for cheeses to be pasteurized even when not required by law.Compulsory pasteurization is controversial. Pasteurization does change the flavor of cheeses, and unpasteurized cheeses are often considered to have better flavor, so there are reasons not to pasteurize all cheeses. Some say that health concerns are overstated, or that milk pasteurization does not ensure cheese safety.[34]

Pregnant women may face an additional risk from cheese; the U.S. Centers for Disease Control has warned pregnant women against eating soft-ripened cheeses and blue-veined cheeses, due to the listeria risk, which can cause miscarriage or harm to the fetus during birth.[35]

Weight loss, blood pressure and blood sugar

A 2009 study at the Curtin University of Technology compared individuals who consumed three servings per day to those who consumed five per day. The researchers concluded that increased consumption resulted in a reduction of abdominal fat, blood pressure and blood sugar.[36]World production and consumption

| This article is outdated. Please update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. Please see the talk page for more information. (November 2010) |

| Top cheese producers (1,000 metric tons)[37] | |

|---|---|

| 4,275 (2006) | |

| 1,927 (2008) | |

| 1,884 (2008) | |

| 1,149 (2008) | |

| 732 (2008) | |

| 594 (2008) | |

| 495 (2006) | |

| 462 (2006) | |

| 425 (2006) | |

| 395 (2006) | |

| Top cheese exporters (Whole Cow Milk only) – 2004 (value in '000 US $)[39] | |

|---|---|

| 2,658,441 | |

| 2,416,973 | |

| 2,099,353 | |

| 1,253,580 | |

| 1,122,761 | |

| 643,575 | |

| 631,963 | |

| 567,590 | |

| 445,240 | |

| 374,156 | |

| Top cheese consumers – 2009[41]  | Total cheese consumption (kg) per capita per year |

| 31.1 | |

| 26.1 | |

| 25.4 | |

| 22.6 | |

| 21.4[42] | |

| 21.0 | |

| 20.9 | |

| 20.7 | |

| 19.4 | |

| 18.9 | |

| 17.4 | |

| 16.7 | |

| 16.4 | |

| 15.3 | |

| 14.8 | |

| 12.3 | |

| 12.0 | |

| 11.3 | |

| 11.0 | |

| 10.9 | |

| 10.8 |

Cultural attitudes

A traditional Polish sheep's cheese market in Zakopane, Poland

Strict followers of the dietary laws of Islam and Judaism must avoid cheeses made with rennet from animals not slaughtered in a manner adhering to halal or kosher laws.[46] Both faiths allow cheese made with vegetable-based rennet or with rennet made from animals that were processed in a halal or kosher manner. Many less-orthodox Jews also believe that rennet undergoes enough processing to change its nature entirely, and do not consider it to ever violate kosher law. (See Cheese and kashrut.) As cheese is a dairy food under kosher rules it cannot be eaten in the same meal with any meat.

Rennet derived from animal slaughter, and thus cheese made with animal-derived rennet, is not vegetarian. Most widely available vegetarian cheeses are made using rennet produced by fermentation of the fungus Mucor miehei. Vegans and other dairy-avoiding vegetarians do not eat real cheese at all, but some vegetable-based cheese substitutes (usually soy-and almond-based) are available.

Even in cultures with long cheese traditions, it is not unusual to find people who perceive cheese – especially pungent-smelling or mold-bearing varieties such as Limburger or Roquefort – as unpalatable. Food-science writer Harold McGee proposes that cheese is such an acquired taste because it is produced through a process of controlled spoilage and many of the odor and flavor molecules in an aged cheese are the same found in rotten foods. He notes, "An aversion to the odor of decay has the obvious biological value of steering us away from possible food poisoning, so it is no wonder that an animal food that gives off whiffs of shoes and soil and the stable takes some getting used to."[47]

Collecting[48] cheese labels is called "tyrosemiophilia".[49]

In the American movie High Society (1956 film), Bing Crosby compares true love to "old Camembert".

See also

Notes and references

- Notes

- ^ Fankhauser, David B. (2007). "Fankhauser's Cheese Page". Retrieved 2007-09-23.

- ^ Simpson, D.P. (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5 ed.). London: Cassell Ltd.. p. 883. ISBN 0-304-52257-0.

- ^ "The History Of Cheese: From An Ancient Nomad’s Horseback To Today’s Luxury Cheese Cart". The Nibble. Lifestyle Direct, Inc.. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ^ Jenny Ridgwell, Judy Ridgway, Food around the World, (1986) Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-832728-5

- ^ "Vicki Reich, ''Cheese'' January 2002 Newsletter". Moscowfood.coop. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ History of Cheese. [1] accessed 2007/06/10

- ^ Notker, §15.

- ^ "British Cheese homepage". British Cheese Board. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-13.

- ^ Quoted in Newsweek, October 1, 1962 according to The Columbia Dictionary of Quotations (Columbia University Press, 1993 ISBN 0-231-07194-9 p 345). Numbers besides 246 are often cited in very similar quotes; whether these are misquotes or whether de Gaulle repeated the same quote with different numbers is unclear.

- ^ Smith, John H. (1995). Cheesemaking in Scotland – A History. The Scottish Dairy Association. ISBN 0-9525323-0-1.. Full text (Archived link), Chapter with cheese timetable (Archived link).

- ^ Cecil Adams (1999). "Straight Dope: How did the moon=green cheese myth start?".. Retrieved October 15, 2005.

- ^ Anon (1 April 2006). "Hubble Resolves Expiration Date For Green Cheese Moon". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ^ McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking (Revised Edition). Scribner. ISBN 0-684-80001-2. p 54. "In the United States, the market for process cheese [...] is now larger than the market for 'natural' cheese, which itself is almost exclusively factory-made."

- ^ a b c Patrick F. Fox, P. F. Fox. Fundamentals of cheese science. Springer, 2000. p. 388. Retrieved 2011-03-21.

- ^ Patrick F. Fox, P. F. Fox. Cheese: chemistry, physics and microbiology, Volume 1. Springer, 1999. p. 1. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ^ "Classification of cheese types using calcium and pH". www.dairyscience.info. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ^ Barbara Ensrud, (1981) The Pocket Guide to Cheese, Lansdowne Press/Quarto Marketing Ltd., ISBN 0-7018-1483-7

- ^ "Classification of Cheese". www.egr.msu.edu. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ^ (McGee 2004, p. 63)

- ^ (McGee 2004, p. 64)

- ^ (McGee 2004, p. 66)

- ^ Nutritional data from CNN Interactive. Retrieved October 20, 2004.

- ^ Center for Science in the Public Interest (2001). "Don't Say Cheese". Retrieved October 15, 2005.

- ^ McGee, p 67. McGee supports both this contention and that more food poisonings in Europe are caused by pasteurized cheeses than raw-milk.

- ^ National Dairy Council. "Specific Health Benefits of Cheese.". Retrieved October 15, 2005.

- ^ The Pharmaceutical Journal, Vol 264 No 7078 p48 January 8, 2000 Clinical.

- ^ "Sleep Study, 2005". Britishcheese.com. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ Cheese Facts, I Love Cheese, 2006. [2].

- ^ Reichelt KL, Knivsberg A-M, Lind G, Nødland M (1991). "Probable etiology and possible treatment of childhood autism". Brain Dysfunct 4: 308–19.

- ^ Christison GW, Ivany K (2006). "Elimination diets in autism spectrum disorders: any wheat amidst the chaff?". J Dev Behav Pediatr 27 (2 Suppl 2): S162–71. doi:10.1097/00004703-200604002-00015. PMID 16685183.

- ^ Lactose Intolerance FAQs from the American Dairy Association. Retrieved October 15, 2005.

- ^ FDA Warns About Soft Cheese Health Risk". Consumer Affairs. Retrieved October 15, 2005.

- ^ Chris Mercer (2005). "Australia lifts Roquefort cheese safety ban".. Retrieved October 22, 2005.

- ^ Janet Fletcher. [3]. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- ^ Listeria and Pregnancy.. Retrieved February 28, 2006.

- ^ Hough, Andrew (2009-10-22). "Eating more cheese 'can help fat people lose weight', study claims". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ^ United States Department of Agriculture for the US and non European countries in 2006 [4]and Eurostat for European countries in 2008 [5]

- ^ Sources: FAO and Eurostat.

- ^ UN Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO)[6]

- ^ Source FAO[dead link]

- ^ "Total and Retail Cheese Consumption – Kilograms per Capita". Canadian Dairy Information Centre. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- ^ Union suisse des paysans, Consommation de fromage par habitant en 2009

- ^ "Cidilait, ''Le fromage''". Cidil.fr. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ Jean Buzby (2005-02-01). "USDA". Ers.usda.gov. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ Rebecca Buckman (2003). "Let Them Eat Cheese". Far Eastern Economic Review. 166 n. 49: 41. Full text.

- ^ Toronto Public Health. Frequently Asked Questions about Halal Foods. Retrieved October 15, 2005.

- ^ McGee p 58, "Why Some People Can't Stand Cheese"

- ^ "Data about largest cheese label collections compiled by the Czech Curiosity Collectors' Club". Klub sběratelů kuriozit (Curiosity Collectors' Club). Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ^ "Cheese label". Virtualroom.de. Retrieved 2010-05-01.[dead link]

- References

- Ensrud, Barbara (1981). The Pocket Guide to Cheese. Sydney: Lansdowne Press. ISBN 0-7018-1483-7.

- Jenkins, Steven (1996). Cheese Primer. Workman Publishing Company. ISBN 0-89480-762-5.

- McGee, Harold (2004). "Cheese". On Food and Cooking (Revised ed.). Scribner. pp. 51–63. ISBN 0-684-80001-2.

- Mellgren, James (2003). "2003 Specialty Cheese Manual, Part II: Knowing the Family of Cheese". Retrieved 2005-10-12.

External links

| Find more about Cheese on Wikipedia's sister projects: | |

| Definitions from Wiktionary | |

| Images and media from Commons | |

| Learning resources from Wikiversity | |

| News stories from Wikinews | |

| Quotations from Wikiquote | |

| Source texts from Wikisource | |

| Textbooks from Wikibooks | |

This audio file was created from a revision of Cheese dated 2006-08-05, and does not reflect subsequent edits to the article. (Audio help)

- Cheese Making Illustrated — The science behind homemade cheese.

- The Complete Book of Cheese at Project Gutenberg

- Cheese.com — includes an extensive database of different types of cheese.

- Cheese at the Open Directory Project

- Cheese Guide & Terminology — Different classifications of cheese with notes on varieties.

- Fresh Cheeses, — Different kinds of fresh cheeses and how to make them.

- Modelling cheese grading- modelling the grade value of cheddar cheese.

- Classification of cheese- why is one cheese type different than another?

| |||||||||||||||||

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar